And how does this influence choices throughout the value network?

Striving for a better world is not only noble but has also become crucial from an economic perspective. However, companies, industries, and consumers sometimes face a paradox in terms of how they can achieve it. In order to make optimal choices, it is essential that all stakeholders have access to reliable information.

People judge whether a product or service is ‘good’ based on an ever-growing number of aspects nowadays. In the past, consumers (and hence manufacturers) were generally satisfied with the best quality for the lowest price. Today, additional factors play a role in the decision-making process, such as whether the item has been produced under good working conditions, whether it is healthy, and even whether the manufacturer supports inclusivity. And, of course, the product or service must not be harmful to the environment.

In short, a product is only considered ‘good’ if it is good for:

– personal and animal wellbeing

– the planet

– your business

The paradox

A thriving economy, social equality worldwide, and a healthy planet are three ambitious goals in their own right. In practice, however, they can lead to contradictions. This is what we call the goodness paradox.

Food waste vs plastic

Let’s take the aim to reduce food waste, for example. One way to do this is to extend the shelf life of fresh produce by packaging it in plastic for extra protection. However, this clashes with the goal of reducing plastic from an environmental viewpoint.

Food waste vs wellbeing

Another widely used method of preserving food is the addition of sugar or salt (or both). While this certainly helps to reduce food waste and increase food safety, it is not good from a people’s perspective. Tempting though they are, large amounts of sugar and salt increase health risks.

There are countless other examples of the goodness paradox in everyday life. It makes it increasingly difficult for businesses and consumers to decide what is ‘good’.

Ever-more challenges, ever-more decision-makers

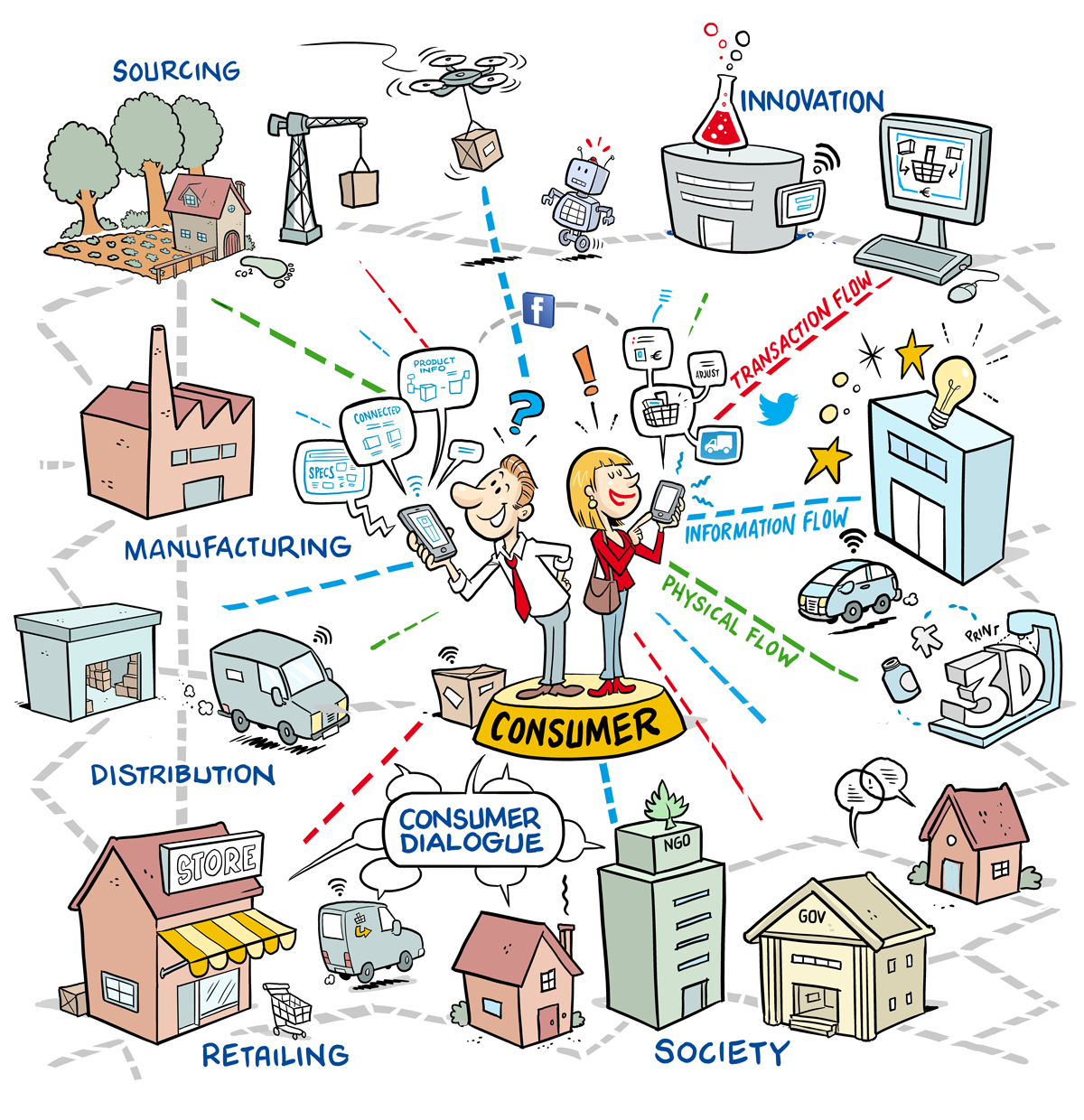

As a result, manufacturers are finding it ever-more challenging to make the ‘right’ choices about their innovation strategies and production processes. From green energy to working conditions and product recipes, all the factors have to be weighed up throughout the entire value network. Moreover, this is not only a challenge inside your organisation; consumers also want access to all this information so that they can make carefully considered choices.

From a manufacturer’s perspective, this means that a new information layer has been added to the value network in which they have to justify their decisions. What further increases the complexity is the fact that retailers and vendors who sell or advise on products often have their own sustainability policies too.

Manufacturers, consumers, and sales partners all face choices:

- The manufacturer: ‘What products do we want to sell and where do we want to source the materials?’

- The consumer: ‘What do I want to buy and consume?’

- Trade partners: ‘Which products do I want to list?’

Information holds the key

The long and the short of it is that every stakeholder in the process – from a board member to a consumer – needs information to make an informed choice, so it is imperative to have access to that data. And while the information about each specific aspect is available somewhere, it is not always stored in a structured manner or automatically shared. In reality, product information ends up scattered throughout the value network.

And yet it is so important to centralize that information. After all, it is essential to justify to consumers (e.g. on the packaging) your choice to add sugar to a product, or to reassure your CFO that you have selected the right supplier that uses green energy even if that is not the cheapest option.

There is no escaping the goodness paradox, but centralizing the provision of information enables every stakeholder to make well-informed decisions in any point of choice. As a result, insight into – and an effective approach to – the goodness paradox is an important key to success… and perhaps even the most important one.